Toulmin, Stephen "The Layout of Arguments"

From RhetorClick

| (One intermediate revision not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

In “The Layout of Arguments,” [[Stephen Toulmin]]’s thesis is that a new framework is needed for argumentation, as an alternative to the syllogism. The framework (or layout) he proposes involves five main components: | In “The Layout of Arguments,” [[Stephen Toulmin]]’s thesis is that a new framework is needed for argumentation, as an alternative to the syllogism. The framework (or layout) he proposes involves five main components: | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Toulmin.jpeg|thumb]] | ||

* A '''claim''' | * A '''claim''' | ||

* '''Data''' supporting the claim and from which the claim can be inferred | * '''Data''' supporting the claim and from which the claim can be inferred | ||

| Line 7: | Line 9: | ||

*'''Rebuttal''' | *'''Rebuttal''' | ||

| - | Toulmin | + | Toulmin's argument is particularly unique because of its attention to the warrant, which is often taken for granted. Toulmin criticizes the syllogism because universal premises such as “All men are mortal” do not properly distinguish between warrant and backing. Additionally, with a syllogism one cannot always tell whether a universal premise is true only in theory or in existential, empirical fact. Toulmin explains that logicians have too long relied on the syllogism and that in doing so they have forced arguments into a mold that doesn’t take into account subtle distinctions. |

| + | |||

| + | Toulmin identifies three types or warrants: authoritative (based on ethos), motivational (based on pathos), and substantive (based on logos). | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Glossary Terms == | ||

| + | |||

| + | The following key terms are defined in the [[Glossary]]: backing, casuistry, modal qualifiers, monotonic reasoning, non-monotonic reasoning, warrant | ||

== Notable Quotes == | == Notable Quotes == | ||

Latest revision as of 02:28, 17 April 2012

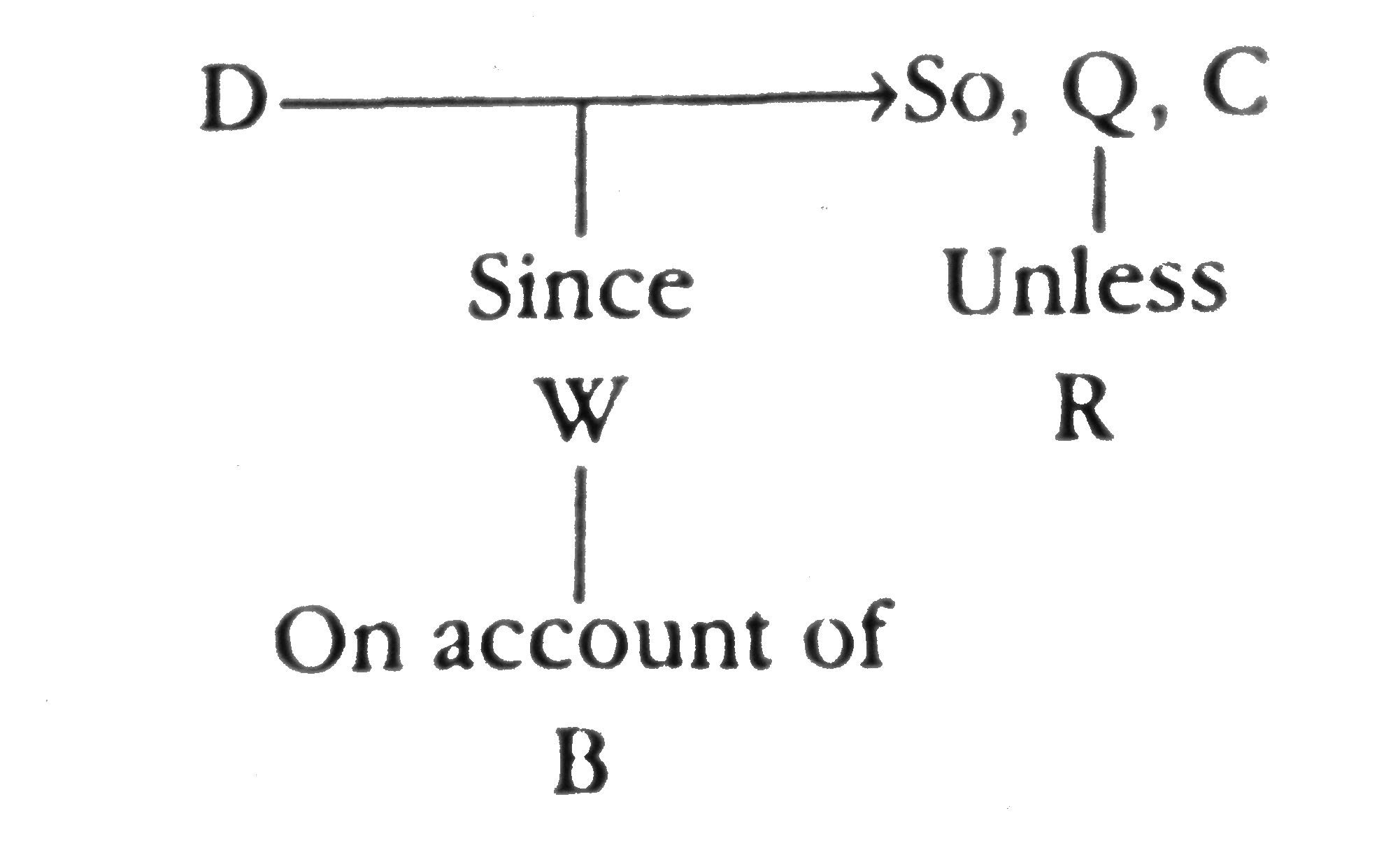

In “The Layout of Arguments,” Stephen Toulmin’s thesis is that a new framework is needed for argumentation, as an alternative to the syllogism. The framework (or layout) he proposes involves five main components:

- A claim

- Data supporting the claim and from which the claim can be inferred

- A warrant, an often implicit assumption that supports the inference of the claim from the data

- A warrant is often supported by a backer, a fact or set of facts that support the warrant

- Qualifications, conditions under which there may be exceptions to the claim

- Rebuttal

Toulmin's argument is particularly unique because of its attention to the warrant, which is often taken for granted. Toulmin criticizes the syllogism because universal premises such as “All men are mortal” do not properly distinguish between warrant and backing. Additionally, with a syllogism one cannot always tell whether a universal premise is true only in theory or in existential, empirical fact. Toulmin explains that logicians have too long relied on the syllogism and that in doing so they have forced arguments into a mold that doesn’t take into account subtle distinctions.

Toulmin identifies three types or warrants: authoritative (based on ethos), motivational (based on pathos), and substantive (based on logos).

Glossary Terms

The following key terms are defined in the Glossary: backing, casuistry, modal qualifiers, monotonic reasoning, non-monotonic reasoning, warrant

Notable Quotes

- "It is at this physiological level that the idea of logical form has been introduced, and here that the validity of our arguments has ultimately to be established or refuted" (105).

- "The existence of considerations such as would establish the acceptability of the most reliable warrants is something we are entitled to take for granted" (115).

- "No entirely general answer can be given to the question, for what determines whether there are or are not existential implications in any particular case is not the form of statement itself, but rather the practical use to which this form is put on that occasion" (123).

- "If we are to set our arguments out with complete logical candor, and understand properly the nature of the 'the logical process,' surely we shall need to emply a pattern of argument no less sophisticated than is required by law" (107).

- "Even the most general warrants in ethical arguments are yet liable in unusual situations to suffer exceptions, and so at strongest can authorize only presumptive conclusions" (125).